For Ky. war hero, wounds are invisible

G.I. struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder after her year in Iraq

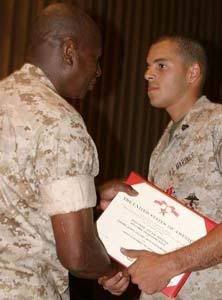

(photo: John Russell / AP) Kentucky National Guard solider

(photo: John Russell / AP) Kentucky National Guard solider

Ashley Pullen holds her Bronze Star citation at her home in

Beaumont, Ky., on Nov. 2. Pullen was awarded the Bronze

Star for helping a wounded soldier during an insurgent

attack while she was stationed in Iraq last year.Spc. Ashley Pullen wasn’t thinking about the dozens of Iraqi insurgents who had just ambushed the convoy. Or their piles of guns and grenades or the bullets ripping through the air around her.

Her bloody comrade lay on the road south of Baghdad, and she had to help the gravely wounded soldier — fast.

So she hustled as quickly as her short legs would carry her, ignoring the heat, the ferocious battle and her heavy gear.

She ran 100, 200, 300 feet — the length of a football field.

It was March 20, 2005, the day Pullen, a member of the Kentucky National Guard’s 617th Military Police Company, became a hero. It was the day that would earn this daughter of small-town America a Bronze Star for valor.

Now, 21 months later, Pullen is a casualty of war, struggling with invisible battle scars.

Pullen is being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder, the result of a year in Iraq marked by harrowing brushes with danger and death — tempered with daily prayers for survival.

Pullen, now 22, doesn’t go out much these days and she says her moods swing for no good reason.

“It’s just an emotional roller coaster every day,” she says. “I have no other way to describe it. I can be a perfectly happy, normal person. Then five seconds later, I will be so mad that I can’t see straight.”

War habits she can't shake Pullen says she has a hard time concentrating long enough to read a book. And she hasn’t totally shaken some habits that made perfect sense in a war zone but don’t translate to the quiet roads of south-central Kentucky.

Sometimes when she drives, she says, her husband, Daniel, notices she’s veering too close to the center line — something she did in Iraq to try to avoid roadside bombs.

“Baby,” he gently warns her, “hellooo ...” Pullen says she once was always smiling, always happy. Then came the war. And everything changed.

Pullen, who joined the Guard at age 17 to help pay for college, didn’t want a desk job. She chose the military police, feeling it better suited someone who “likes to be to in the middle of everything.” In Iraq, she found herself in the thick of explosions, gunfire and mortar attacks.

The ambush that turned her into a hero started on a steamy March morning just outside Baghdad. Here’s how Pullen remembers it:

She was driving one of three Humvees providing security behind a 30-vehicle convoy when the crackle of gunshots and the boom of rocket-propelled grenades suddenly filled the air. Pullen’s unit moved ahead to counterattack, flanking the insurgents so they couldn’t escape.

Pullen got out of her Humvee and braced herself against the back of it. She and other soldiers unleashed a torrent of gunfire and grenades on 40 to 50 insurgents attacking from a nearby orchard.

She could see the enemy clearly, armed with dozens of AK-47s, machine guns and grenades. Pullen blasted away with her M-4 rifle, emptying a 30-round magazine, then reloaded and opened fire again.

“You don’t have time to be scared,” she says. “You just have time to react. ... The fear doesn’t set in until later when you say, ‘Oh my God, what happened?’ ... When the bullets start flying, you’re saying OK, ‘I want to live through this’ and you do everything you can to survive.”

Answering a radio call — “Everybody’s down! I need help” — Pullen backed up her Humvee part way, then ran about 300 feet to a gravely wounded sergeant, who was screaming and rocking in agony. (Pullen says she didn’t pull her truck next to him, fearing that would create a bigger target for the insurgents.)

Dodging bullets, she dropped to her knees to help her comrade. “It hurts! It hurts!” he yelled. She got him out of his bloody vest, lifted his shirt and saw a single slug had pierced his stomach through his back, leaving a hole the size of a quarter.

Pullen tried to bandage and calm him. “Think of green grass and trees and home,” she said. “Think about your little boy. Think about ANYTHING but here.” Pullen was herself thinking of the first blush of spring at her Kentucky home. “I don’t know if that comforted him, but it worked for me.”

As she was tending to the sergeant, a medic from her company fired a shoulder-held rocket launcher at a sniper’s nest. “Back blast clear!” he shouted, a warning to stay far away. But Pullen was close enough to touch his leg. She blanketed her body — all 5-foot-2 — over the wounded sergeant to protect him. The blast knocked her on her backside.

When it was over, at least 26 insurgents were dead and six were wounded. Three civilians in the convoy also were killed. The three wounded members of Pullen’s company all survived.

The insurgents’ arsenal, according to a military report, included 35 AK-47s and machine guns, 16 rocket-propelled grenades, 39 hand grenades, 175 full or empty AK-47 magazines, 2,500 loose rounds — and a video camera with footage of the ambush.

Pullen was awarded a Bronze Star with the V device for valor. (Several other soldiers in the unit also were honored, including Sgt. Leigh Ann Hester, who was given the Silver Star — the first woman to receive that award since World War II — for her bravery. She killed at least three insurgents.)

'Incredible courage'In a recommendation for Pullen’s medal, her company commander wrote: “Tremendous dedication and focus. Credited with saving the life of a team leader that day. Incredible courage.”

Pullen served seven more months in Iraq, learning to cope in a world where the threat of death was a daily fact of life.

“You get up in the morning, you say your prayers and you hope to God that you come back that night,” she says in her soft lilt. “You kind of get numb ... which was my way of coping. You just kind of shut everything off and become a robot. Emotions get you nowhere. They get you in trouble. ... It’s hard to come back and be normal.”

When she returned home last fall to Edmonton, Ky., her mother, stepfather and uncle — all Desert Storm veterans — praised her as a hero. Pullen doesn’t buy it.

“You got to do what you got to do,” she says. “I didn’t have a choice in the matter. If you see an accident on the road, you’re going to stop and make sure everything is OK. ... It’s my job.”

But Pullen also says the emotional strain of doing her job began wearing on her while she still was in Iraq. She had nightmares that zombies and Iraqis were coming after her.

She noticed her own dramatic personality transformation — from easygoing to “this huge, flaming ball of anger.” She says she tries to rein in her emotions around her three younger sisters and two younger brothers. “It’s hard for me to explain to them, ’It’s not your fault I’m mad,”’ she says. “They try to understand.”

Her father does, too. “He says just forget it,” she explains. “I say, ‘Dad, you can’t forget it. You just have to learn to live with it.’ ... He doesn’t want this to haunt me and hold me back the rest of my life — being just 22 years old.”

Reminders at home of life abroadPullen says even now, she doesn’t go out alone. When she’s on the road, familiar sights like overpasses can be frightening because they remind her of where the enemy lurked.

Pullen leans heavily on her husband. They’ve been sweethearts since they met at an after-school program at age 15.

“God bless my husband, he tries,” she says. “I know it puts him through hell.” There are days, she says, when she calls him at work and says: “’I need you here. Come home.’ I am just bursting out in tears for no reason. ... I need that lifeline.”

Daniel says he had his own anxiety attacks when his wife was in Iraq. When she called, he says, “You always had the worry — this may be the last time I ever talk to her. What should I say?”

Pullen has been seeing a psychiatrist twice a month. At each visit, the doctor talks to her, then turns to Daniel. “How is she doing?’ the doctor asks.

“He can pick up on things I don’t notice,” Ashley Pullen says.

Daniel says sometimes the smallest gestures in the morning — a goofy grin or a silence — indicate whether it’ll be a good or bad day for his wife.

The two are preparing for the birth of their first child — a son — who is due this month.

Meanwhile, Pullen stays close to home with family, far from the world that caused her so much emotional turmoil.

“I don’t watch the news,” she says. “I don’t want to hear about it. I don’t want to see it. I don’t even like the word Iraq.”